History

This website primarily deals with the most up-to-date techniques and methods for fossil preparation. However, it is important to have an understanding of the history of the field. Fossils collected in the 19th and early 20th century will have been prepared with many techniques and materials mentioned no longer in use, but an understanding of these collection and preparation methods can be useful in determining how to mitigate damage or deterioration from aging materials and older preparation and conservation techniques.

While some of the materials and technologies used now in fossil preparation would probably astound the early practioners of the field, many of the tools and techniques would still be recognizable to them. Together, these two facts are a reminder to us that not all old techniques are harmful and that equally even the best of our modern methodologies may look hopelessly outdated in a hundred years’ time.

Spanish explorers documented large bones showed to them by Native Americans in the 16th century and fossils even were collected by Thomas Jefferson, who kept a collection in the White House during his Presidency. His ground sloth Megalonyx jeffersonii was the subject of the first and second scientific articles on fossils ever published in the United States. In 1842 the word dinosaur was coined by the British anatomist and paleontologist Richard Owen and in 1865 Joseph Leidy of the Academy of Natural Sciences described the first dinosaur fossil from the United States.

Edward Drinker Cope

(1840-1897)

A world-renowned naturalist, Edward Drinker Cope was expert in all groups of vertebrates, both living and fossil. He named over 1,000 previously unknown species of vertebrates, from fishes to mammals, most of them living. While expert at collecting, preparing and analyzing fossils, Cope made unwise personal investments that required him, near the end of his life, to sell his massive personal fossil collection to cover his debts. The collection was purchased by the American Museum of Natural History, becoming the nucleus of the world’s largest collection of fossil vertebrates.

Dinosaur bone collecting in the American West increased in the 1870s, culminating in the “Bone Wars” between O.C. Marsh and Edward Cope. Their ugly rivalry was considered, both at the time and today, a blot on the name of science, but nevertheless resulted in the beginnings of important dinosaur collections at the Yale Peabody Museum and the American Museum of Natural History.

In the mid-19th Century, collectors would normally would gather fossil fragments that were visible on the ground’s surface. A collector might dismount from his horse, look for additional fragments, place them in his saddlebag and ship them to their paleontologist clients with minimal packaging. Back in the lab, hundreds of small fragments with little to no accompanying information would be laboriously pieced back together by preparators.

Paleontologist John Bell Hatcher was one of the first collectors to develop a more systematic field collecting process that recorded the type, position and orientation of fossils while they were still in the ground – information that was vital when it was time for the fossil to be prepared. In areas like the American West, the expansion of railroads meant that collectors were no longer reliant on pack animals or wagons for transporting specimens, permitting collection of larger, more complete fossils and protecting them better during transport.

Paleontologist John Bell Hatcher was one of the first collectors to develop a more systematic field collecting process that recorded the type, position and orientation of fossils while they were still in the ground – information that was vital when it was time for the fossil to be prepared. In areas like the American West, the expansion of railroads meant that collectors were no longer reliant on pack animals or wagons for transporting specimens, permitting collection of larger, more complete fossils and protecting them better during transport.

By the turn of the 20th century, the institutional setting for American vertebrate paleontology had settled into large, urban museums well supported by their communities and patrons. A fierce competition among museum paleontologists to display spectacular new mounted fossil vertebrates ultimately led to the modernization of American fossil preparation. Simultaneously, other less visible, but equally important, fossils were collected across the country, from mammals and fishes to marine invertebrates and plants.

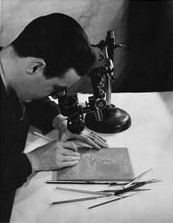

During this period, the largest museums launched ambitious expeditions aimed at collecting exhibit-quality dinosaurs, which netted an enormous quantity of unprepared fossils. Getting these fossils into suitable shape for scientific study and public display presented a number of challenges for fossil preparators.

- Laboratories - New material arriving from the field required room for temporary storage and large dedicated laboratory spaces in which to prepare it. Adapting an existing basic fossil preparation lab to the needs of dinosaur paleontology often involved considerable extra investment in equipment and space. Read more…

- Staff - Finding, training and retaining skilled fossil preparators became increasingly expensive. The sheer volume of work, and its unique demands, led to increased specialization and professionalization among the science support staff. Read more…

- Techniques - Preparators developed important lab innovations and new techniques to handle the workload, some of which required expensive new machinery, entirely new systems or new spaces in which to operate the equipment, some of which produced particularly noxious dust, noise, or smells. Read more…

By 1908, the second American Jurassic dinosaur rush was essentially over. Mounted dinosaur skeletons proliferated widely in the aftermath of the bone rush. Giant sauropod dinosaurs were mounted for display in New York, Pittsburgh and Chicago, and more would quickly follow. Another, less visible, but just as lasting legacy of the rush was the modernization of American fossil preparation. Large public museums ultimately provided ample, dedicated lab space, along with the requisite money, equipment and personnel to do fossil preparation properly. Likewise, the demand in museums for a large number of cutting-edge, mounted dinosaur exhibits created a mandate for innovation, and for newer, better, and more efficient techniques for streamlining the work while improving the results. Preparators began to specialize and professionalize – a process that continues to this day. For more information visit this site's pages on how to become a preparator and professional development.

Resources

- Text was and adapted excerpted from Paul Brinkman’s 2009 paper “Dinosaurs, Museums, And The Modernization of American Fossil Preparation At The Turn Of The 20th Century” in Proceedings of the First Annual Fossil Preparation and Collections Symposium (complete reference below). To read more in depth about the second fossil wars and the development of fossil preparation at the American Museum of Natural History, The Chicago Field Museum and Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Museum download the complete text here.

- Download Adam Hermann’s articles to learn more about his techniques and materials:

- Download Peter Whybrow’s 1985 article on the History of Fossil Collecting and Preparation Techniques here.

- Visit the Academy of Natural Sciences’ online exhibit on Joseph Leidy and learn more about the challenges of early collecting and fossil preparation.

- Access archive images of expeditions, field notebooks and portraits from the American Museum of Natural History’s Division of Paleontology collections archive page.

- View additional historical images on exhibitions and expeditions from the American Museum of Natural History’s archives.

Bibliography

Aaseng, Nathan. 1996. American Dinosaur Hunters. Springfield, NJ: Enslow.

Brinkman, P. 2009. “Modernizing American fossil preparation at the turn of the 20th century”. Methods in Fossil Preparation: Proceedings of the First Annual Fossil Preparation and Collections Symposium, Brown, M.A., Kane, J.F., and Parker W.G. Eds. pp.21-34.

Brinkman, Paul D., 2000. “Establishing vertebrate paleontology at Chicago’s Field Columbian Museum, 1893-1898”. Archives of Natural History 27:1 pp.81-114.

Colbert, Edwin H. 1984. The Great Dinosaur Hunters and Their Discoveries. New York: Dover.

Hermann, Adam, 1909. “Modern Laboratory Methods in Vertebrate Paleontology”, Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 26, pp. 283-331.

Hermann, Adam, 1908. “Modern Methods of Excavating, Preparing and Mounting Fossil Skeletons”, The American Naturalist 42:493 pp. 43-47.

Kissel, Richard A. 2007. “The Sauropod Chronicles” Natural History April pp. 34-38.

Osborn, Henry F. 1904. “On the Use of the Sandblast in Cleaning Fossils” Science n.s.19 no:476 p.256.

Riggs, Elmer S. 1903. “The Use of Pneumatic Tools in the Preparation of Fossils”, Science n.s. 17 no 436. pp. 747-749.

Rixon, A.E., 1976. Fossil Animal Remains: Their Preparation and Conservation. London: Athlone Press.

Spalding, David A.E. 1993. Dinosaur Hunters. Rocklin, CA: Prima.

Whybrow, Peter J. 1985. “A History of Fossil Collecting and Preparation Techniques” Curator 28:1 pp.5-26.